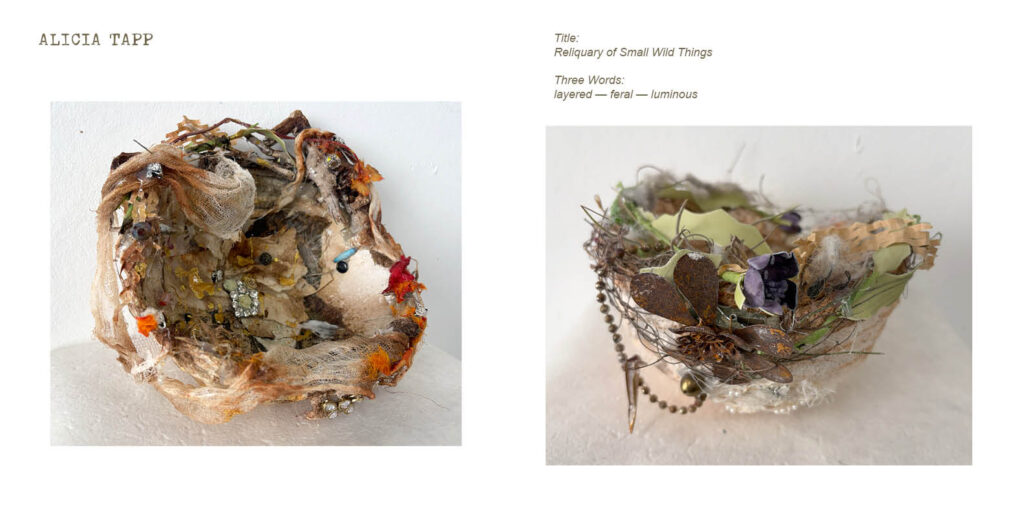

Can these images be part of a conversation with each other?

I am so excited to be part of the upcoming Piecework collage exhibition at Gallery Prudencia. The generous response to my collage work in the Taos exhibition reminded me how deeply people connect to layered imagery — how instinctively they lean in when fragments suggest a story without fully explaining it. That experience nudged me back toward collage as a kind of universal language.

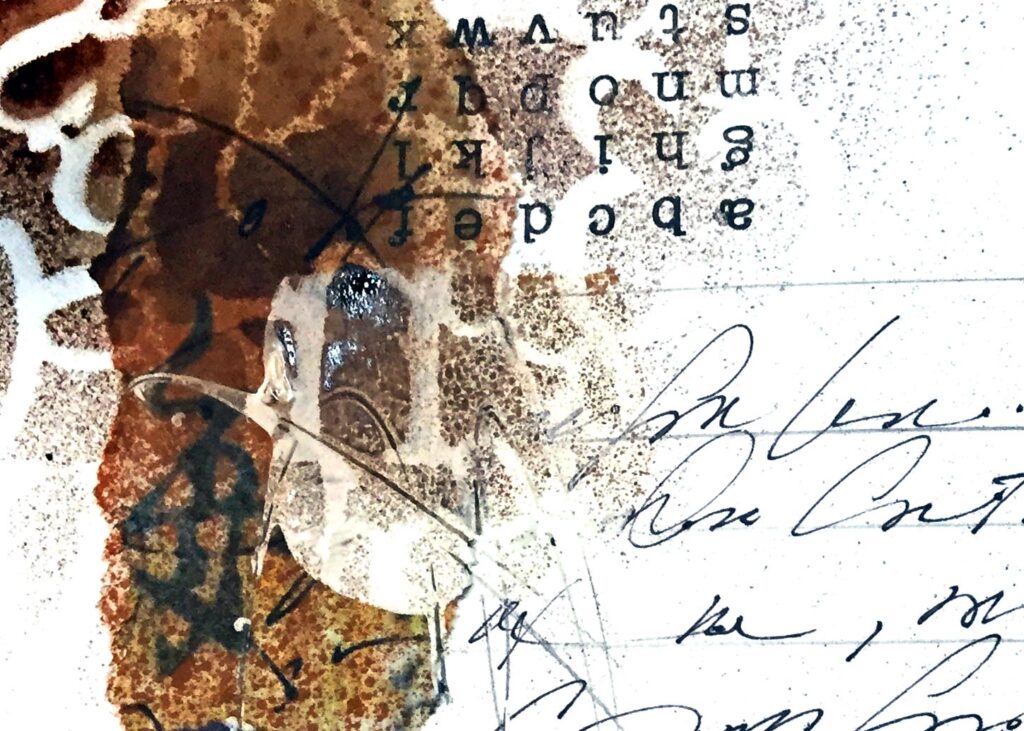

For years, I’ve been drawn to “shards” — not as broken pieces, but as clues to something larger that once existed. Collage (particularly encaustic collage) allows those fragments to speak again. A child’s gaze, a bird poised between shadow and light, a torn scrap of handwriting — these become visual syllables in a language built from juxtaposition and pause.

Collage does not declare; it suggests. Returning to collage feels like returning to that essential impulse: to gather fragments, to listen for the conversation between them. Below are three collages that will be in the group show at Prudencia. This small series is called “Conversations.” I love to work in series!

The Secret, Encaustic Collage, 2026

This first collage in the Conversations series is called “The Secret.“

Who is telling the secret to whom?

At first glance, the most literal reading is that the child is whispering to the bird. The dove rests in the hand, close to the mouth — a confidant. Birds have always been messengers, carriers of news between realms. So perhaps the child entrusts the bird with something fragile — a memory, a fear, a wish.

But then the dynamic shifts.

The bird may be whispering to the child. Its beak is near the lips, not the ear. The exchange is intimate but ambiguous. Is the bird delivering news? A prophecy? A truth the child is not yet ready to fully understand?

And then there is us. Perhaps we are holding the bird!

The child’s gaze is direct. Unblinking. The eyes are not turned toward the bird — they look outward. Toward the viewer. Which raises another possibility: the secret is being shared with us. The bird is intermediary, but the child knows we are watching. We become part of the exchange. Isn’t it fun to interpret collage as conversation?

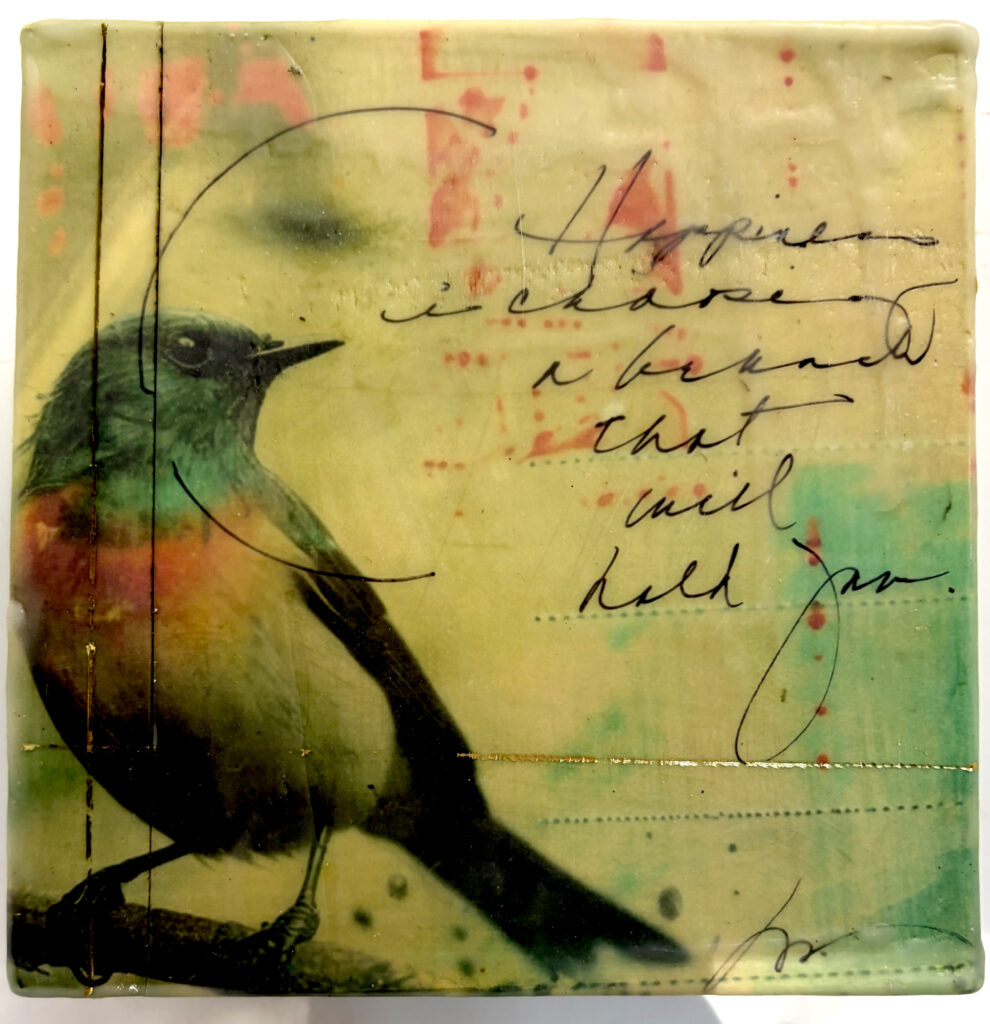

The First Right Answer, encaustic collage, 2026

If The Secret is a whisper shared outward, The First Right Answer, second in the series, feels inward — almost instructional.

Who is speaking here?

The girl’s gaze is lowered. Unlike the first piece, she is not looking at us. She is listening. Her face tilts toward the bird, but there is no theatrical gesture. The conversation is quiet, concentrated. The moment feels suspended just before comprehension.

The bird, darker and more angular than the dove in The Secret, feels less like a carrier of innocence and more like a voice of discernment. Its beak is pointed, alert. The metallic copper shape cutting across its body suggests signal or transmission — like a tuning fork, a frequency.

So perhaps:

- The bird is giving the answer.

- The girl is receiving it.

- Or the answer is emerging between them.

But the title complicates everything.

“The First Right Answer” implies that there will be others. It acknowledges process. Trial. Error. Learning.

In collage, the direction of the gaze alters the conversation. In The Secret, the child looks outward, implicating the viewer in the exchange. In The First Right Answer, the child looks inward, receiving something only she can recognize. Collage allows these subtle shifts to suggest entirely different kinds of dialogue — confession versus recognition, projection versus intuition.

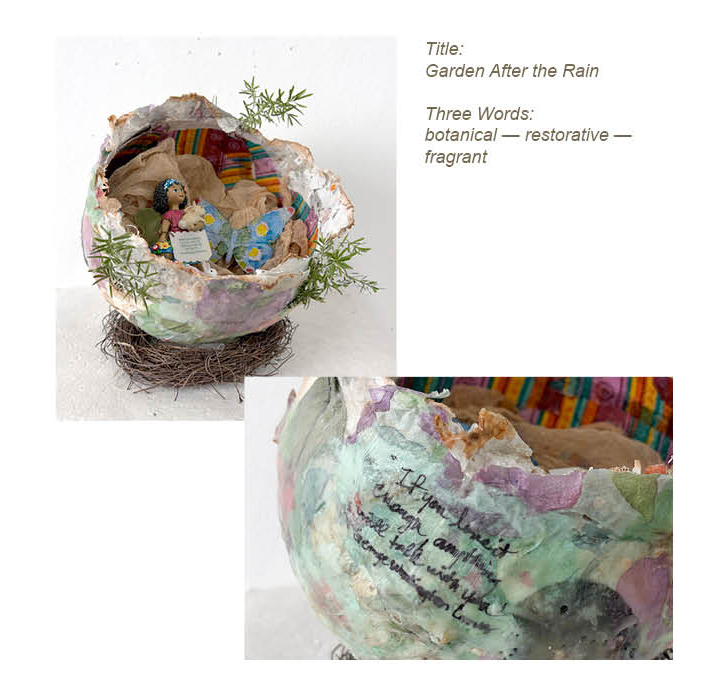

The Dilemma, encaustic collage, 2026

If The Secret is a whisper and The First Right Answer is a recognition, then The Dilemma is the moment of choice.

And here the child looks directly at us again. But this gaze is different from The Secret. It isn’t confiding. It’s searching. Measuring. Almost asking.

Who is speaking in this piece?

Now there are two birds — a black one and a white one — facing each other. They are positioned below the child, like embodiments of opposing voices. Instinct and restraint. Shadow and light. Risk and safety. Memory and possibility.

Unlike the earlier works, the conversation is no longer between human and bird. It is between birds — while the child observes. Or perhaps the birds are projections of her internal dialogue. The title shifts everything.

“The Dilemma” implies tension without resolution. There is no “right answer” yet. No secret successfully delivered. Only the presence of two equally compelling voices.

________________________________________________

Honestly, I had no notion of these conversations when I started on these pieces, but as I worked, they started talking! I tend to work one piece at a time – this keeps the conversation contained in its own “room.”

So if collage can be a conversation, then it is never finished when I step away from the studio table. It continues in the gallery, in the pause between viewer and image, in the stories people quietly bring with them. What I learned in Taos — and what I hope to experience again at Gallery Prudencia — is that these fragments are not mine alone once they are assembled. They become meeting places.

A bird may carry a secret, or offer the first right answer, or argue both sides of a dilemma — but the meaning settles differently for each person who stands before it. That is the gift of collage. In a world that often feels fractured, perhaps there is something deeply human about gathering the pieces and letting them talk to one another — and to us.

2518 N Main Ave. San Antonio, Texas 7821

The Opening Reception for the Piecework exhibition at Gallery Prudencia will be held on Saturday, March 7, from 2 to 4 pm. You will be able to meet the artists on Saturday, March 28, from 2 to 4 pm., with the Artist Talk beginning at 3 pm.

Come have a conversation about collage with the artists — Kim Collins, Nancy Hall, Mary James, Billy L. Keen, Lyn Belisle (me), Sara McKethan, Tim McMeans, Marcia Roberts, Steven G. Smith, Stefani Job Spears, Sheila Swanson, Cris Thompson, and Bethany Ramey Trombley.

♥Lyn

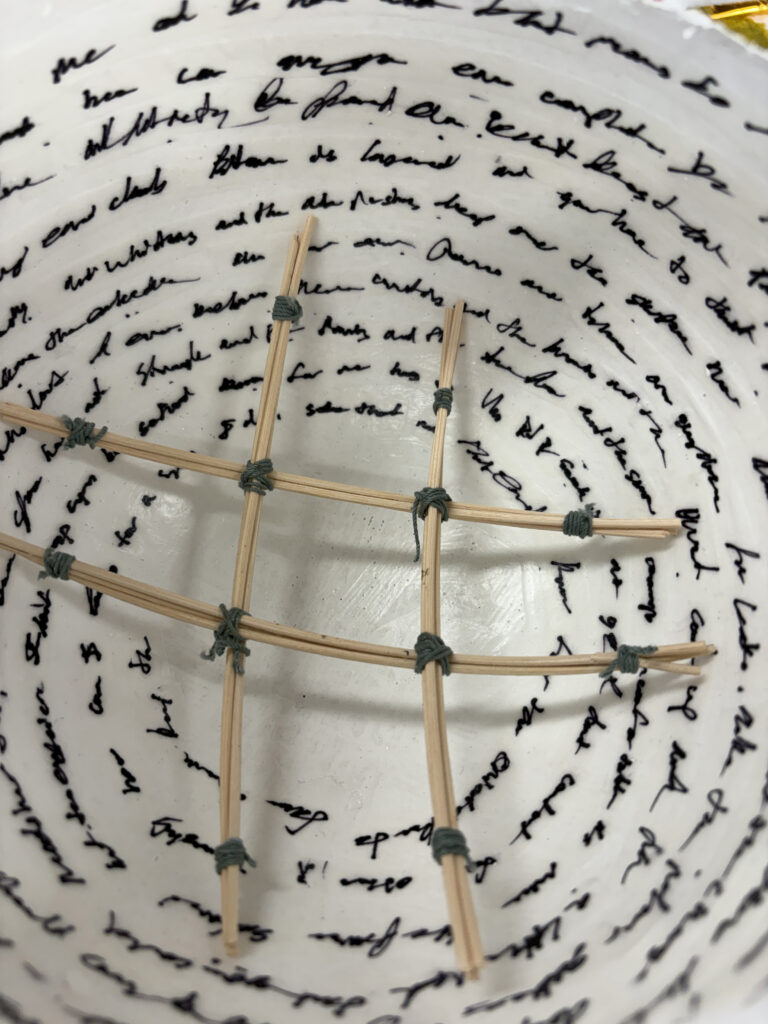

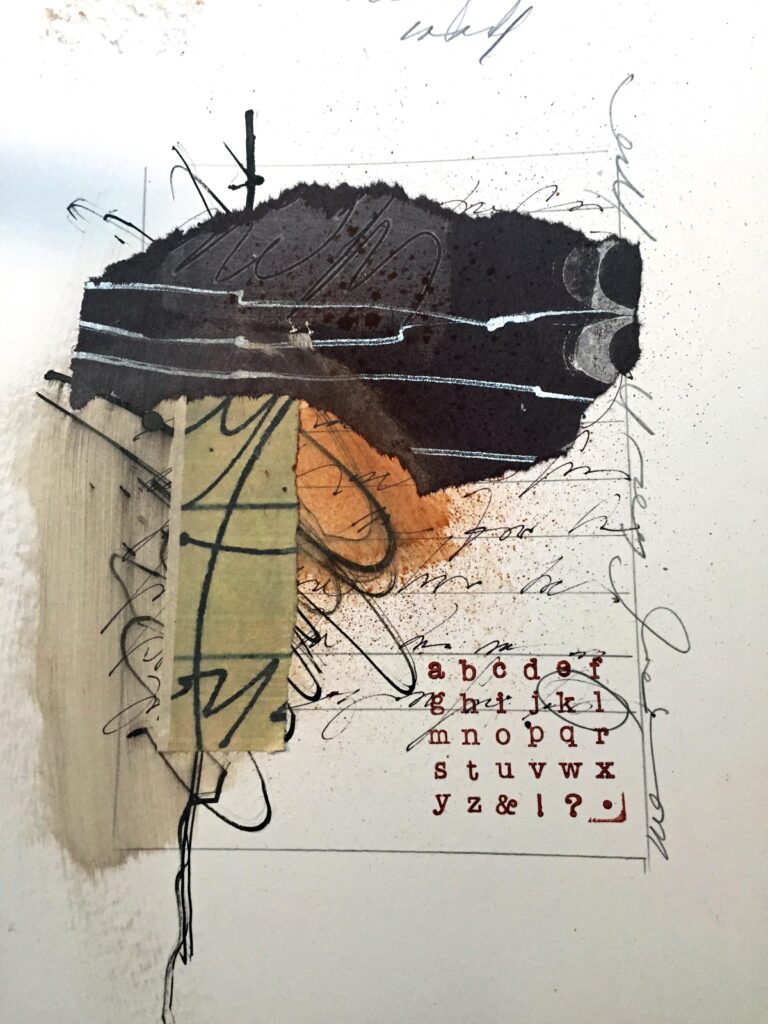

PS And if you want to play with collage, below are two sheets that you can copy, paste, print out, tear up, combine with other pictures, magazine photos,old book pages, and whatever it takes to create your own collage conversation.(If you can’t see them,click on p.2)

What a long title for a post! Read on . . . .

What a long title for a post! Read on . . . .